Retrofit City-Making: A multimedia exploration of vertical occupation in Cape Town

The vast majority of literature on informal occupations focuses on why and how residents occupy vacant land, incrementally developing informal structures to address their basic needs, namely the need for a home.

Occupations have been, and continue to be, a dominant mode of city-building in cities in the Global South, driven primarily by a need for housing in cities gripped by perpetual housing shortages. This article contributes not only to this debate on city-making and occupations but also to the limited theorisation of vertical occupations – the occupation of abandoned buildings – in South Africa.

Vertical occupations, as opposed to horizontal (vacant land) occupations, in the South African context have been observed and theorised primarily in Johannesburg’s inner city district. Referred to in the literature as ‘hijacked’ and ‘dark’ buildings, and as ‘bad’ or ‘problem’ buildings in policy discourses (such as in this paper by Winkler, and this by Wilhelm-Solomon), vertical occupations have until recently occurred primarily in abandoned privately owned buildings.

We offer up a look at an unusual case of South African occupation; unusual in the sense that the occupation under study entails the occupation of a vacant state-owned building, namely a hospital situated in the inner-city. This occupation constitutes a citizen-driven effort to‘re-appropriate’ public assets. It's unusual as it occurs in Cape Town, where ‘hijacked’ buildings are uncommon and is considered to be part of a wider occupation movement in the city.

Using documentary photography and interviews with residents, we argue that this occupation reflects a logic of ‘retrofit city-making’. We show that, through processes of reconnecting, re-purposing and renovating, dwellers retrofit a space, previously designed by the state for a very different use, to fit their needs and desires.

Vignettes of Retrofitters

The site focuses on the case of a hospital building in Cape Town’s Woodstock area. Almost three years ago Reclaim the City, a social movement made up of housing activists, evictees and working class people occupied the abandoned Woodstock hospital renaming it Cissie Gool House after anti-Apartheid activist Zainunnisa “Cissie” Gool. At present Cissie Gool House is home to over 900 people. The majority of occupiers are originally from Woodstock and occupied Cissie Gool House because they don’t want to leave Woodstock, preferring the challenge of making their own homes in the abandoned hospital, and living in very close proximity to their fellow occupiers rather than moving to the Cape Flats. This story provides the backdrop for the everyday stories of occupiers and retrofitters, as they work to shape the city.

Eesha Alexander prays in a section of the former hospital outside his home that has been repurposed as a place for Islamic prayers. At prayer times throughout the day various people utilise the space. The prayer area is in one of the newly occupied areas of the hospital. It doesn’t get a lot of foot traffic as there are only two families further down the corridor making it ideal for prayers. Additionally, when people first started occupying they avoided that area out of superstition because it is close to where dead bodies were washed.

Jonathan Karelse's home is visibly a hospital ward. The curtains that used to act as dividers between hospital beds now divide his home into two rooms, one for two of his children and another for him, his wife and their youngest baby. He has carved space for him and his family out of discarded medical materials.

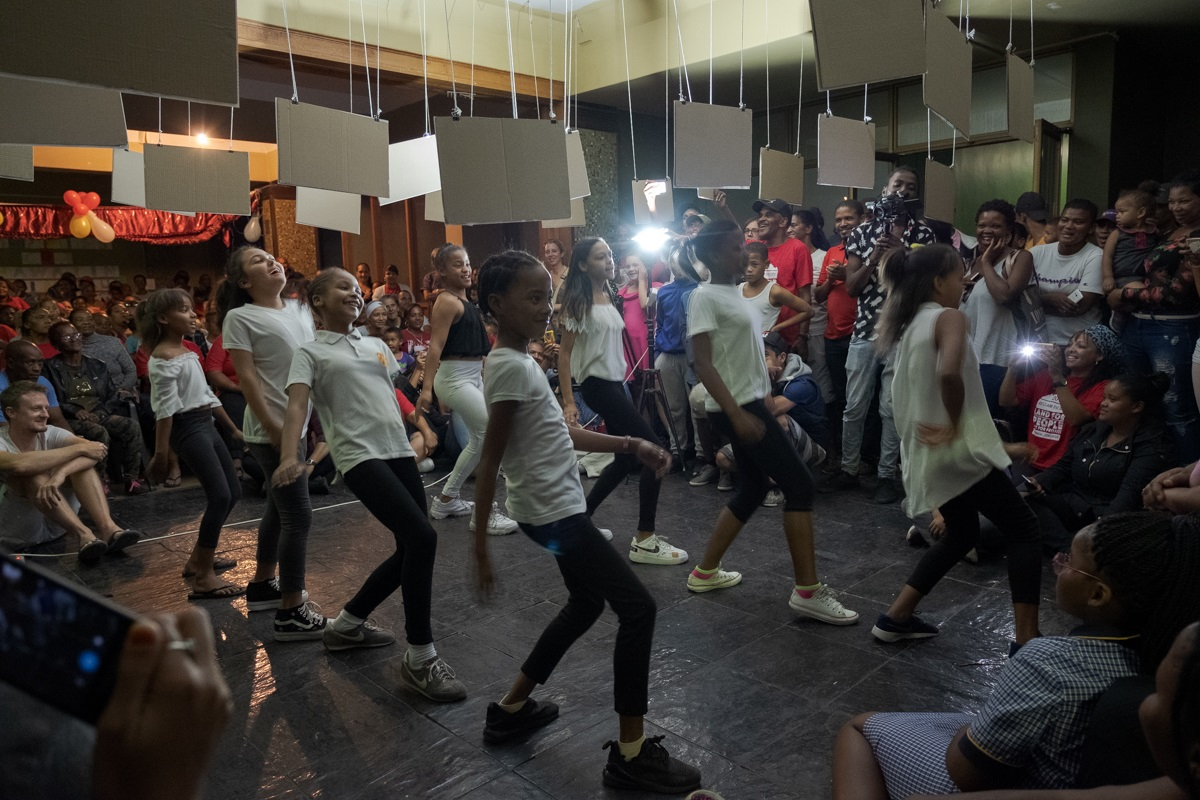

The hall on the ground floor of the former nurse's quarters is being used to host events of all kinds, from Eid celebrations to yoga classes. In this photograph Reclaim the City celebrate their two-year anniversary in this hall. The site is being re-purposed by occupiers and activists.

Maxine Voilet White and her partner have made many renovations to their home to make it liveable. As can be seen in the photograph, they broke through the wall between two rooms to extend their place, and are in the process of building a shower as funds become available. They are engaged in ongoing retrofit to shape the space to serve their needs.

As the hospital was abandoned nearly all the electrical wiring and copper piping was removed and sold. It was common to see basins with no piping for instance. When occupiers moved in they would often have to run electricity into their homes using long extension leads as well as using rubber piping to run water into their homes. Here we see a former operating theatre that was re-purposed as a laundry room with a washing machine connected to both power and water.

These vignettes provide insights into how people, coming together into groupings of families and communities, some with a stronger activist intent than others, have retrofitted the hospital site, re-purposing it to suit their contemporary needs from washing to worshipping.

A future for retrofitting

As cities become more densely built and available vacant land more peripheral and scarce, the retrofit of underutilized buildings, particularly through bottom-up actions such as occupations, will become an increasingly important mode of urban development. It is now, more than ever, imperative that we think about how people redevelop spaces as central to the urban project, both materially and conceptually. Urban scholars and built environment professionals will need a wide range of skills to engage with these emergent practices. They will need to refrain from simplistic extremes, such as a hyper-romanization or vilifications of the actions and actors involved. They will need a deeper understanding of these processes, their material effect, the power dynamics which shape them, and the ways in which these sorts of practices fit into city-wide processes.

It is, after all, through the countless actions of individuals that cities are made, every day, in new and different ways. Understanding the everyday processes through which this has taken place, enhances our understanding of occupations and incremental retrofit as city-making.

The medium we have used for this project allows for these everyday practices to be foregrounded and understood in richer and more creative ways. The next steps of this project include using images taken and interviews conducted by Barry Christianson to develop an exhibition at the hospital site for the residents. We are also planning to develop this blog into a longer academic reflection on retrofit city making and a teaching case study which can be used in curriculum at the African Centre for Cities.

Barry Christianson is a documentary photographer and photojournalist based in Cape Town, South Africa.